Explore the weird and wonderful world of bacteria in Oxford

Bacteria tend to get a bad name – but the new Bacterial World exhibition at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History sets out to change our minds about these tiny yet fascinating organisms.

They’re the oldest form of life on Earth, they account for as many as three quarters of all species, and they’re found practically everywhere on the planet (including inside our bodies!). But most of us know very little about bacteria – including how much they do for us.

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History’s Bacterial World exhibition aims to set the record straight. Packing around 37 billion years of history into 55 exhibits, the exhibition looks at the many ways these organisms (the smallest creatures considered to be alive) shape life on Earth as we know it.

Artist Luke Jerram’s inflatable E. coli sculpture looks perfectly at home at the Bacterial World exhibition

Perhaps the most striking – and certainly the largest – exhibit on show is the 28m-long, inflatable sculpture of E. coli by artist Luke Jerram. Suspended from the ceiling, its alien appearance and spiky trailing tendrils look surprisingly at home among the museum’s elaborate neo-Gothic ironwork.

Even E. coli itself, best known for causing food poisoning, has been used by scientists to produce insulin, helping countless diabetics – just one of the many examples of how bacteria has changed the world, revealed in this fascinating exhibition.

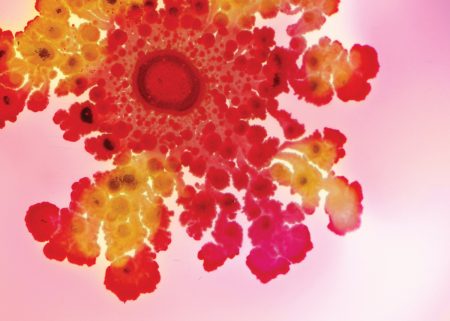

Streptomyces by Mark Buttner

As visitors will discover, fewer than 100 species of bacteria harm humans by causing infectious diseases. Most are either harmless to us, or actively useful. In fact, bacteria are the reason we’re here at all. Some 2.4 billion years ago, bacteria learned to harness the sun’s energy, producing oxygen as a by-product – and paving the way for all the oxygen-breathing species that came after.

Today, bacteria supply nitrogen that helps our crops to grow, they break down and recycle our waste, and the bacteria in our gut play a big role in our overall body and brain health. As a matter of fact, our bodies contain as much bacteria as they do human cells.

Love sourdough? Thank Lactobacillus, the magic ingredient. Hate plastic waste? Exciting discoveries such as Ideonella sakaiensis, a bacterium that can eat certain types of plastic, may offer a route to tackle the pollution problem.

Life less ordinary

Bacteria lead surprisingly complicated lives of their own. We now know that they sense, communicate and remember. Some bacterial communities cooperate with each other, while others wage microscopic wars with chemical weapons and spears.

Many live in complex relationships with their plant and animal hosts, such as the bioluminescent bacteria that allow many sea creatures to glow in the dark, or the ‘man-hating’ Wolbachia, parasites with the power to skew the populations of their insect hosts in favour of females.

Visitors will discover plenty of these weird and wonderful creatures at Bacterial World – alongside quirkier exhibits, such as beautifully crocheted portraits of bacteria grown on everyday objects, such as wedding rings and dirty socks.

Penabacillus strain

Bacterial World is perhaps the most ambitious and modern exhibition yet for the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. A short stroll from Oxford’s many other attractions, this atmospheric museum has all the stuffed animals, dinosaur bones and fascinating fossils you’d expect. It was here that Darwin’s theory of evolution was first publicly (and heatedly) debated in 1860; preserved off-show are the fragile remains of one of the last dodos on the planet, which inspired Lewis Carroll to write this long-extinct bird into Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It’s a treasure trove of science and Victorian design in a city with more than its fair share of great museums.

Bacterial World will be on show alongside the permanent collection until 28 May 2019, with a lively programme of accompanying talks and events.